Robert A. Williams

Attorney, Williams, Luck & Williams

Martinsville, Virginia

(b. 1944)

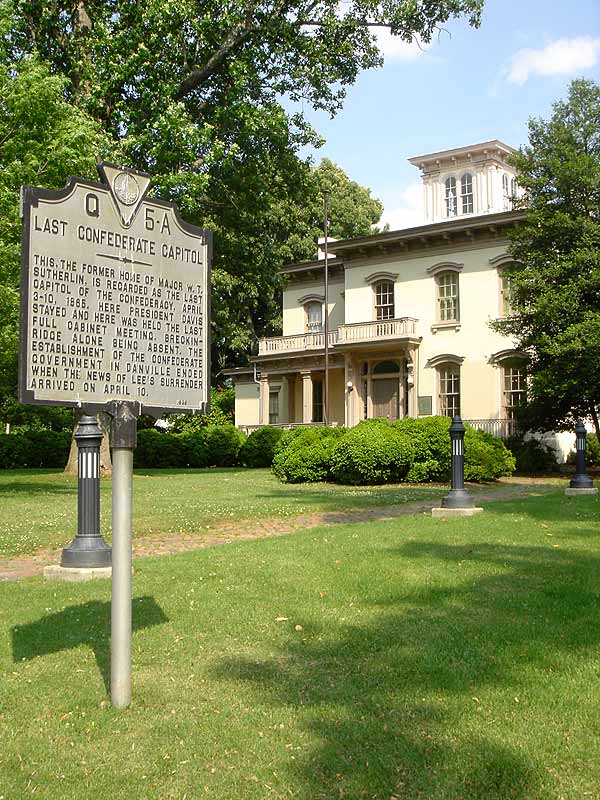

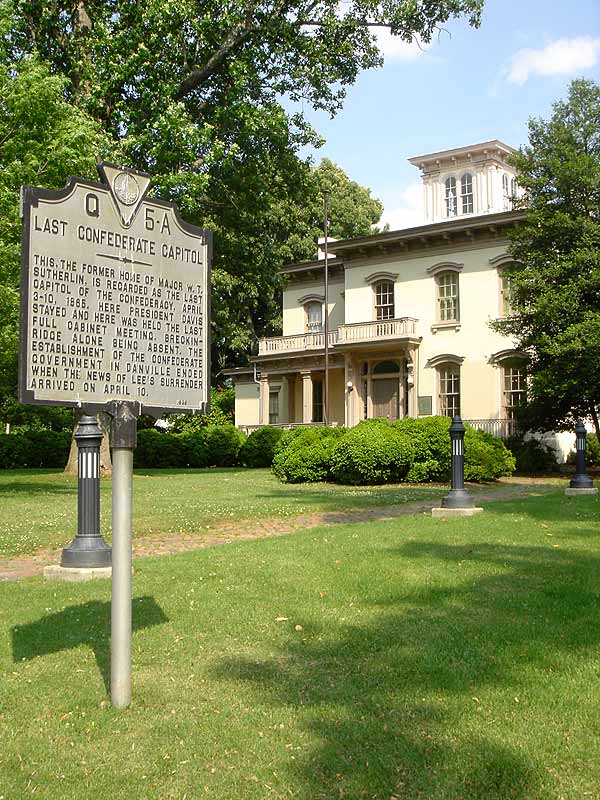

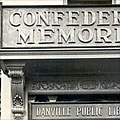

Robert A. Williams led a 1960 sit-in at the segregated Danville Memorial Library, above, now the Danville Museum of Fine Arts and History.

Photo: Laurie Ripper

On April 2, 1960, Mr. Williams and fifteen youths from the Loyal Baptist Church appeared at the all-white Danville Memorial Library, located in a mansion memorialized as the “Last Confederate Capitol.” The black students asked to take out books; the librarian refused, saying the library was closed. The students sat down briefly then left. The next week, they requested reading cards and privileges at the white library, only to be directed to the poorly equipped African-American branch. The students then held a mass meeting at Loyal Baptist Church, attended by 350 people. The local NAACP voted to seek a federal court order to integrate the library and an injunction to prohibit the segregation of public facilities.

“My father was well aware of what was going on. We had discussions about the legal aspects of the sit-in demonstrations and what we could use [the NAACP attorneys] for and what type of support we could garner from the NAACP Legal Defense Fund in suing if [city authorities] denied us access.”

—Robert A. Williams

- Interview Excerpts

- Related Resources

- Biography

The selections below come from oral histories of Robert Williams conducted by Emma C. Edmunds on March 25, 2000, in Mr. Williams’s law office in Martinsville, Virginia, and by University of Virginia students Gladys Hairston (College ’04) and Laurie Ripper (Law ’05), on August 4, 2004, also in Mr. Williams’s law office. The first interview focused on the 1960 student-led efforts to desegregate the Danville Public Library (now the Danville Museum of Fine Arts and History) and Ballou Park. The second included a more extensive discussion of the network of NAACP attorneys in Virginia, as well as reflections on the city of Martinsville and its racial history. Both provide insights into Mr. Williams’s father, NAACP attorney Jerry Williams, his actions, and his philosophy.

Segregation: The Protests of Jerry Williams, Sr.

Jerry Williams, Sr., refused to allow his family to attend segregated public facilities.

Photo: Courtesy of First State Bank

My father was a strong force in our lives. My father and mother. I remember my father very particularly. As kids growing up, we could not participate in anything that was segregated. I remember one time my brother and I slipped and went to one of the segregated theaters. When we came home, we got a spanking for it and were put on some restrictions. I don’t think at that young age we realized how great a network my father had in Danville. Whenever anything happened with us, he would always know. Somebody would come and tell him, even though the town at the time was 30,000 folks. So he would not let us participate in any segregated activities. We couldn’t go to the theaters. We couldn’t do anything that had anything to do with segregation. He was very strong in his sense that we should not participate in segregated activities.

Student Protests: 1960 Sit-ins Inspire Danville Youth

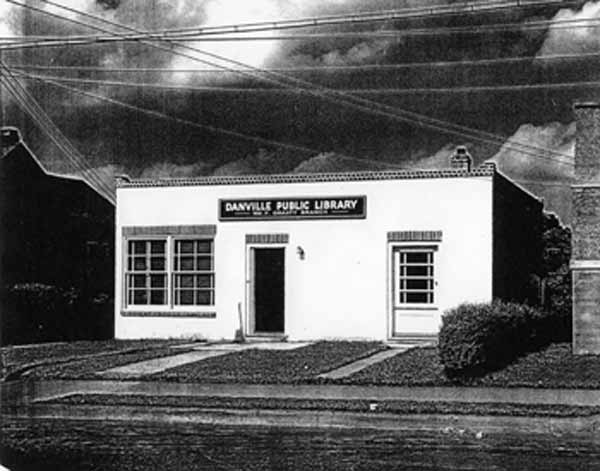

In 1960, this small branch of the Danville Public Library served the African-American citizens of Danville.

Photo: Courtesy of Della Barton

There were sit-in demonstrations by four A&T students at the Woolworth’s in Greensboro that garnered a great deal of national attention because of their efforts to desegregate the lunch counters. That, of course, affected most black youth across the country, who had to face these segregated situations. We began discussing what we could do in Danville. One of the persons who was in high school at the time was a Chalmers Mebane, and he was a veteran as I recall. He was older than any of the other high school students. I think he was probably a junior or a senior. He got involved in the NAACP meetings. We would meet after school at Loyal Baptist Church to discuss what we wanted to do. I think Chalmers Mebane probably was the one who wanted to sit in at lunch counters in Danville.

Because of my history and familiarity with the law, and based on dinner conversations with my father and his conversations with other friends about what was possible and what we could accomplish through law, I was able to convince the other students who were in the Youth Division of the NAACP and our adviser that the first attack we should have [should be] against the public parks and the public library, because those were publicly funded. There was precedent that if you had institutions that were publicly funded, that we’d have a greater chance of integrating those than lunch counters, which were owned by private corporations or individuals. …

We didn’t have to go through any training as did a lot of the kids that sat in at lunch counters in terms of taking the insults. We planned what we were going to do, the routes we were going to take, and the objects that we were going to fight against in terms of the public park and the public library. At the time, Ballou Park was set up for whites only. I think there may have been a couple of parks that were for blacks. The public library was at the—where it is now—the last capitol of the Confederacy, which was right at the corner of Holbrook Avenue and Main Street. There was a division of the library that was on Holbrook Street that was for blacks and that was in a very, very small building. It may have had three rooms at the time. There was very little space to spend a lot of time studying and viewing the books.

The president of the NAACP at the time was Reverend Doyle J. Thomas [Sr.], who was the minister of Loyal Baptist Church. He sat in on a number of the meetings that the students had in planning the sit-ins. Doyle was very much familiar with it. I call him Doyle now, but, of course, at that time he was Reverend Thomas. My father was well aware of what was going on because I, of course, had discussions with him. We had discussions about the legal aspects of the sit-in demonstrations and what we could use them for and what type of support we could garner from the NAACP Legal Defense Fund in suing if [city authorities] denied us access to those institutions—the park and the library.

Last Capitol of the Confederacy: A Seminal Place

In 1960, the library for whites was located in this mansion, memorialized in the marker as the Last Confederate Capitol.

Photo: Laurie Ripper

The main library building was a seminal place and had a great deal of significance—the fact that … it was in the last capitol of the Confederacy. …

I have no specific recollections about that day except that we got together as we had planned. … We were at Ballou Park first. … The police came and closed the park. There were no arrests made at that time. We all had anticipated that they were going to close the park. We didn’t know whether or not we were going to be arrested. I’m sure there were some provisions that were made that if we had gotten arrested we could be bailed out of jail.

Once they closed the park, we then proceeded to the library. That meant coming back down West Main Street, coming into Main Street, and going straight to the library and into the library. Soon after we went into the library, that institution was closed, too. [Laughs.] So it was a—. We felt on that day, very, very triumphant—that we had accomplished what we wanted—that was that if we could not use the park and the library, then they would be closed to all.

NAACP Attorneys: Local, State, and National Connections

Ruth Harvey was among the NAACP attorneys who filed suit to desegregate the Danville Public Library.

Photo: Courtesy of Fred Motley

There’s no doubt about it. The legal framework had been put in place before the demonstrations went on. I’m sure that my father and the other lawyers in Danville had made calls to the lawyers in Richmond, who had made calls to the lawyers in New York, to say, “This is going on and this is something that we want to fight.” It was clearly an effort where there was planning in a sense. They knew about it. They knew which ones [suits] they were going to support and which they weren’t going to support, because resources were very scarce at the time.

The NAACP attorneys in Danville represented blacks in adjoining counties and connected to attorneys throughout the Commonwealth and the nation. The organization was particularly strong in Virginia, winning teacher equalization cases in the 1940s and playing a major role in the Brown v. Board of Education desegregation suit in 1954. They also served as role models for youngsters, such as Robert Williams, who knew them.

Of course, across Virginia at that time you had a number of figures who became very prominent in the civil rights movement, from Oliver Hill in Richmond to Sam Tucker in Richmond, Martin A. Martin, and—I’m trying to think of his name now—he became a judge in Washington on the Federal Court of Appeals [Spotswood Robinson].

All of these were people that I knew simply because my father had always taken the family to the meetings of the lawyers. You knew them all. They all participated. They all would join in on these suits. They would do the research. They would help out and would always have the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund participate by providing the money to support the lawsuit. It was clearly a joint effort—by a cadre of lawyers who themselves were unafraid and who themselves also faced retribution around the state because of their participation in the civil rights movement—from the cases that led to Brown v. Board all the way through the desegregation of the public schools in Danville. …

The meetings of the black lawyers of Virginia were all over Virginia. It was the Old Dominion Bar Association. They would meet in Richmond. They would meet in Tappahannock. They would meet all over. We would know the lawyers on a social level, but we couldn’t sit in the meetings. … It was only in the evenings, during the social hours, that we would see them. A number of these gentlemen, and there were a few women, but a number of the gentlemen were poker players, so we would always see them playing poker after the meetings, and so we got a chance to know them because of watching them play poker after the meetings. …

These people were friends. They watched me grow up. I watched them get older, and as a result, you form fast friendships. Indeed, that’s how I happened to know Doug Wilder very well before he became governor. He had participated in the Old Dominion Bar Association. There were so few black lawyers you could count them on two hands and two feet. You got to know all of them across the state. … For me, it was very heady because I saw what they had been able to accomplish. I knew that I could do it. … They were wonderful role models.

Robert W. Williams, interviews by Emma C. Edmunds, March 25, 2008, and by Gladys Hairston and Laurie Ripper, August 4, 2004, transcripts, Danville Community College, Danville Public Library, and Mary Blount Library at Averett University, Danville, Virginia.

Click on the image thumbnails below to view a larger version of the image.

Intersecting Networks: First State Bank Board Members.

Jerry Williams, Sr., far right, served on the board of Danville’s First State Bank, a minority-owned and -operated institution. He is pictured here with, left to right, William B. Muse, president and CEO of Imperial Savings and Loan, Martinsville; Edward G. Adams, an insurance agent; L. Wilson York, then a cashier at the First State Bank (later president and CEO); M. C. Martin, president and CEO of the bank; and N. T. Williams, a real estate agent. In 1960, following the NAACP student sit-in at the all-white library, Mr. Martin and local NAACP leaders issued a statement of intent to enjoin the city to integrate facilities supported by taxpayers. His brother, Richmond attorney Martin A. Martin, later joined with local NAACP lawyers Jerry Williams, Andrew Muse, and Ruth Harvey to file a lawsuit to enjoin the city from denying citizens the right to use the library on account of race.

Courtesy of First State Bank. Danville, Virginia.

Last Capitol of The Confederacy.

In 1858, a Richmond architect built this lavish structure as a home for William T. Sutherlin, banker, tobacco factory owner, entrepreneur, onetime Danville mayor, and a delegate to the Virginia Secession Convention in 1861. Mr. Sutherlin had purchased the property from his friend and business associate, merchant Levi Holbrook, a Northerner who had relocated to Danville. The Sutherlin mansion is located on Main Street, which bisects a roadway named for Levi Holbrook into segments—one African-American (Holbrook Street) and one white (Holbrook Avenue). Jefferson Davis made the Sutherlin mansion his headquarters in the final week of the Civil War, giving Danville the epithet, “Last Capital of the Confederacy.” Ironically, Levi Holbrook was also in residence, having taken refuge at his friend’s home because of his open Union sympathies; while living in the house, Mr. Holbrook made his alliance clear, taking food to Union soldiers in the Danville prisons. After the death of Mr. Sutherlin’s widow, the Confederate Memorial Association and the local chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy led a successful drive to save the Sutherlin home from demolition and donated the structure—which came to be regarded by some whites as a Confederate “shrine”—to the city. For its efforts in saving the house, the UDC was awarded upstairs quarters in the mansion in perpetuity. The first floor served as the white public library. In 1974 the library moved, and the mansion became the Danville Museum of Art and History. [Sources: Frederick F. Siegel, The Roots of Southern Distinctiveness: Tobacco and Society in Danville, Virginia, 1780–1865 (The University of North Carolina Press: Chapel Hill and London, 1987); Mary Cahill and Gary Grant, Victorian Danville: Fifty-two Landmarks: Their Architecture & History (Mary Cahill and Gary Grant: Danville, 1997); James Robertson, “House of Horrors: Danville’s Civil War Prisons,” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 69 (1961), 329–46.]

Courtesy of Laurie Ripper. 2004.

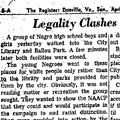

Legality Clashes with Reality: Danville Register Editorial (1960).

One day after the NAACP youths appeared at the Danville Public Library, the Danville Register published this editorial, characterizing the students’ action as an invasion of a hallowed space. “Instead of using their own Langston Library, or even the Branch Library staffed by their own race, they chose to invade the Confederate Memorial Mansion, and on April 2—the 95th anniversary of JEFFERSON DAVIS’ departure from Richmond for Danville.” In its conclusion, the editorial states that, despite U.S. Supreme Court rulings to the contrary, “race mixing at all public facilities” was not “acceptable” in the Southern city and, therefore, “cannot happen.” [Read "Legality Clashes with Reality" editorial text.]

Courtesy of the Danville Register. April 3, 1960.

Celebration Of the Confederacy (1965).

In 1965, the city of Danville held an extravagant Civil War centennial celebration, including a parade, reenactments, dances, and speeches marking the residency of Jefferson Davis in Danville. Officials such as U.S. Senator A. Willis Robertson extolled the past and linked Southern opposition to the voting rights bill before Congress to “states’ rights” struggles a century earlier. The Danville branch of the NAACP and the Danville Christian Progressive Association issued a statement deploring the celebration. The elected officials pictured here were waiting for a ceremony to start at the Sutherlin Mansion, where Davis had resided. From left, U.S. Senator A. Willis Robertson; “Dan” C. Daniel, state delegate and later U.S. representative; former Governor William “Bill” M. Tuck, then U.S. representative from the Fifth District; Virginia Senator Landon R. Wyatt; and Virginia Attorney General Robert Y. Button. [Source: Danville Register, April 2–4, 1965.]

Courtesy of Leon Townsend. Danville Register. April 4, 1965.

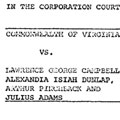

Jerry Williams Cross-Examines Police Chief Mccain.

On September 19, 1963, the trials of Danville civil rights protesters and leaders got under way in the Danville Corporation Court, with Judge Archibald M. Aiken presiding. Danville NAACP attorneys Jerry L. Williams and Andrew C. Muse were among the lawyers representing the protesters. This excerpt focuses on the testimony of Danville Police Chief Eugene G. McCain and his account of the events of June 5, 1963. Direct examination was by commonwealth’s attorney Eugene Link. Jerry Williams cross-examined Chief McCain.

1963 Danville (Va.) Civil Rights Case Files. Testimony. [view .PDF version]

Robert A. Williams is a partner with his brother, Jerry, in the law firm of Williams, Luck, and Williams, founded by their father, Jerry Williams, Sr., with offices in Martinsville and Danville. Robert Williams was born in Danville, and raised in the Holbrook-Ross neighborhood. Influenced by the political involvement of his father, a Danville and NAACP attorney, he was active in the Youth Division of the NAACP and, in the wake of the student sit-ins in Greensboro, N.C., participated in efforts to desegregate the all-white Danville Public Library and Ballou Park. He attended Howard University from 1962 through 1966, and the University of Virginia Law School from 1966 through 1969. As one of only a few minority law students, Mr. Williams played an active role in urging U.Va. administrators to recruit and enroll more African-American and female students.