James W. Peters, Jr.

Owner, L. H. Brooks & Bro.

Funeral Directors (b. 1930)

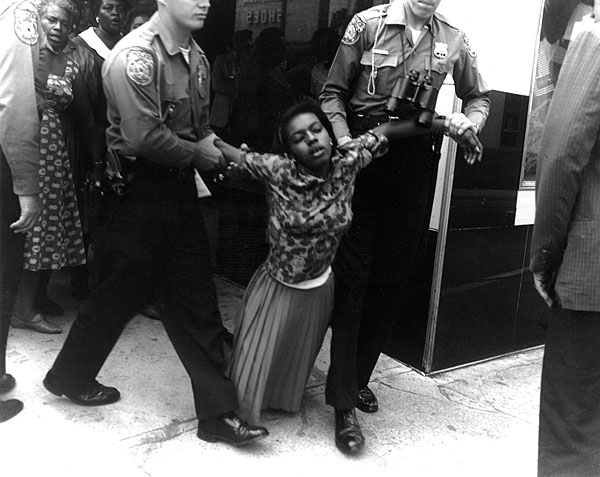

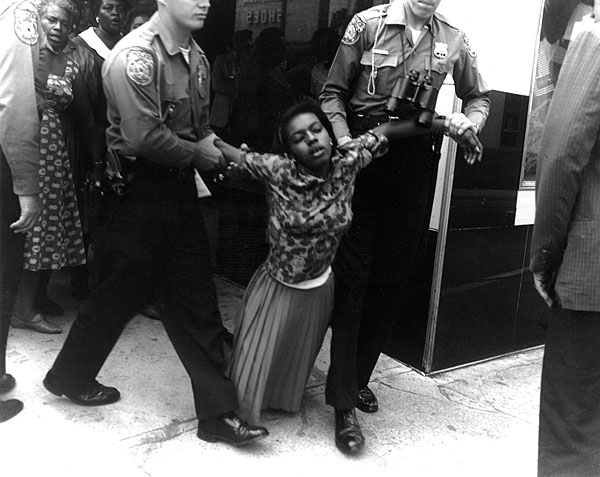

James W. Peters helped secure bonds for arrested protesters, such as the young woman above.

Photo: Leon Townsend,

Danville Register

When civil rights demonstrations started in Danville in May 1963, Mr. Peters helped line up African-American property owners who would be willing to post bonds for the release of the more than 300 protesters who were arrested and jailed that summer. Eventually, African-American residents posted up to $300,000 in property bonds to secure the freedom of their fellow citizens. The repressive legal tactics of the white authorities and the violent response of police and deputized garbage men to a June 10, 1963, peaceful prayer vigil helped unify the African-American community and its leaders, who had been divided on the timing of street demonstrations.

“The black community came together, especially after the first signs of violence that took place. In the very beginning, there was some hesitation, but then after they realized what was going on, they said, ‘No. We are going to be part of this.’”

—James W. Peters, Jr.

- Interview Excerpts

- Related Resources

- Biography

These selections come from oral histories of Mr. Peters conducted by Emma C. Edmunds in Danville, Virginia, on October 11, 2003, and November 15, 2003.

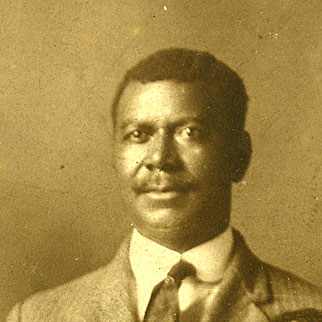

African-American Entrepreneur: L. H. Brooks

L.H. Brooks, the half-uncle of James W. Peters, Jr., started L.H. Brooks & Bro. Funeral Directors.

Photo: Courtesy of Nannie G. Armstrong

In the early twentieth century, Mr. Peters’s family moved to Danville from Henry County to seek employment in the tobacco factories. His half-uncle, L. H. Brooks, attended mortuary school in Pittsburgh, Pa.; started L. H. Brooks & Bro. Funeral Directors; was a member of Loyal Baptist Church; and in 1919 became a founding director of First State Bank. Mr. Peters’s paternal grandmother, Charlotte Flood Brooks Peters, once lived in a two-story house on Holbrook Street (245 Holbrook Street, he believes, though the structure is no longer standing). In this selection, Mr. Peters recalls his family’s early history in Danville.

My grandmother [Charlotte Flood Brooks Peters] had fourteen children. … Uncle L. H. [Brooks] was her youngest child by her first husband. My dad was her oldest child by her second husband. They were very close. When Uncle L. H. started the funeral business, my father, who was living in New York at the time, was his financial backer and put up the money for him to operate the business. When Uncle L. H. died in 1929, my grandmother was the executor of his estate. She prevailed upon my father to leave New York City and come to Danville to protect his financial interest. His [L. H.’s] full name was Louis Henry Brooks. My father’s father’s name was Edward Peters.

It was my understanding that they moved to Danville around 1900, primarily to seek employment. They moved to Danville from Henry County, where my father and Uncle L. H. were born. Grandma had some relatives here who told them they could move to Danville and there could be some employment for them, primarily with the tobacco factories.

Like most kids at the time, they wanted to do something that was better. Uncle L. H. wanted to be better than being a tobacco worker. He went off to Pittsburgh—which was the location of one of the mortuary schools at that time—to take up a trade and he did. And he came back home and he started the business.

When they first came here, I’m not sure [exactly where they lived], but I remember [when] they lived on Holbrook Street. I want to say 245 Holbrook. The house is not there anymore. We still own the property but—. At the time that I can remember, my grandmother lived there, her daughter Beatrice, and her two children. It was a big two-story house and it had the fireplaces all through the house for the warmth from the winter.

Segregation: African–American Property Owners

Mr. Peters's maternal grandfather, George Chaney, lived at 220 Ross Street in the Holbrook-Ross neighborhood.

Photo: Emma C. Edmunds

Mr. Peters’s maternal grandfather, George Chaney, was employed as a cook and domestic worker for a white family. He owned 220 Ross Street, and Mr. Peters cites him as a remarkable example of how African Americans survived and acquired property on a meager income. This section grew out of a conversation between Emma Edmunds and Mr. Peters about how, in Danville in 1963, African Americans accumulated enough wealth to post more than $300,000 in property bonds for those arrested during the Danville civil rights protests. Until 1948, Mr. Peters’s immediate family also lived at 220 Ross Street.

A lot of the folks who worked and lived in Danville were depending on the tobacco markets for their living. Most of the people only earned $9 to $10 a week, and how they were they able to support their family, send their children to school, and build, or to buy and build homes, and support their churches and their lodges and whatever else—. It was just amazing that they were able to do this.

My own grandfather, George Chaney, was one of those who didn’t work in the tobacco factories, but he worked as a domestic. He was a cook. But he supplemented his income with caning chairs and raising chickens and getting the eggs and whatever else he could possibly do to save and to do what he needed to. Then again, his wife gave birth to thirteen children, of which only two lived to be grown. But those two did very well. One of them was my mother. [Laughs.] But it’s amazing to me as to how they were able to do so many things with so little.

He primarily was a cook, and at home we had chickens. He got them and raised them from birth all the way through the fryer stage and the broiler stage and then the laying stage. We always had some chicken and eggs at home. In our yard, there were several peach trees, apple trees, a grape vine, a pear tree, and those fruits were either used to make wine or dried for pies for later in the winter. And so there was plenty there for us …

He instilled upon me to make the most out of what you had. You know, it didn’t necessarily mean that you had to go out and buy the latest apple or pie or pear. You had it right there in the yard. You ate those and be satisfied with that.

Founder of the Movement: Charles Kenneth Coleman

Charles Kenneth Coleman, a Danville educator, fought for teacher salary equalization.

Photo: Danville Commercial Appeal

Active in the Danville Voters League and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), Charles K. Coleman fought for teacher salary equalization, one of the early civil rights issues in Virginia. According to Mr. Peters, he was dismissed from his job as a teacher for his activism, but refused to abandon his battle for equal rights.

Charles Coleman was a teacher in the Danville public school system. He was fired because he was asking for equalization of salaries between black and white. After that, he became the carrier for the black newspapers, the [Richmond] Afro-American and the [Norfolk] Journal and Guide. He was going around the city delivering those different papers. This is during the time you had to pay poll tax. If you paid your first year, it was only $1.50 per year and you continued to pay. If you got to be twenty-four years old before you first registered, then you paid interest. [Laughs.] I think it was $4.50 or something like that —$3.95 or $4.50 you had to pay plus your $1.50. You had to pay that money to go back in order to register.

So what Professor Coleman did, in going around in various parts of the city, he carried a little notebook with him and different people would give him fifteen cents, a quarter, or whatever until they got enough money to be able to pay that poll tax. He’d record it and would carry them down to get [registered]. He was a history major, so he was able to school them enough on whatever questions that the registrar was going to ask so they could get qualified. He got enough folks registered when he decided that he was going to run for city council. He ran for city council and lost by 60 or 75 votes, somewhere in that neighborhood; he had enough registered people to ( ) along with that. In the next two years when he went to run again, all the whites had voted one way and he lost by almost 500 votes. It was just one of those things that was stacked against him. … We would have to say that he was the actual founder of the movement.

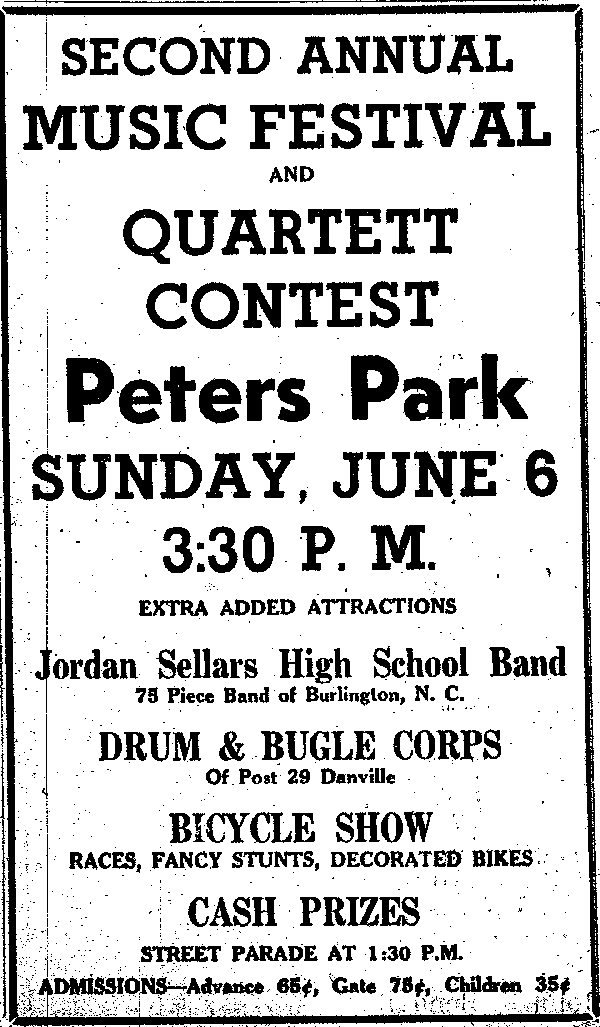

Segregation: Peters Park for African-American Competitions

During segregation, Peters Park was the site for African-American baseball games and other events.

Photo: Danville Commercial Appeal

Mr. Peters’s father, James W. Peters, Sr., built Peters Park in 1948 for African-American baseball competitions and other events; he borrowed $100,000 from the white-owned American National Bank to finance the park, according to his son. Mr. Peters, Sr., also financed the payroll of the Danville All Stars, an African-American team, in the late 1940s.

Dad and another fellow, Ted Wilson, sponsored a baseball game. They would catch the touring black team coming through and they would get them to stop and play in Danville. They used to rent a space at the white baseball park and would get secure dates when the white team was not going to be there. They had two teams that were coming in and they, the white team, had a rain date and they cancelled his ability to have those games, so he had two teams that he had to pay something for their coming. He promised himself that that would be the last time that would happen. So he and Ted built the park; officially the name was Almagro Stadium Corporation. Ted eventually dropped out. Dad bought his interest out. From that point, he built the baseball stadium.

And incidentally, it was a first–class place at that time. It had—the lights that they had on it were the second-best lights in the country. The lights in it were better, were supposed to be, than the Cleveland, Ohio, stadium, which had just been put in the year before; this was supposed to be the next set of lights. Then he sponsored a local and then a touring team for the first year and then another one of the touring teams came through from Jacksonville—the All Stars they were. They had a good crowd. The manager, Jim Williams, prevailed on Dad to be the sponsor for the team, and so he sponsored the team. They changed the name to the Danville All Stars and they traveled up and down the roads to wherever, but they always came home to play. They had a little Carolina League that they played in and days they weren’t, they would be on the road. Dad made the payroll for it. Payroll ’47, ’48, ’49 was running right at $1,500–$1,800 a … month. …

People were working in the tobacco factories at that time making $9 a week, so it was big salary … I mean it was something else. That went on for several years and then Jackie Robinson made the major leagues and television became the prevailing thing; people could stay home and watch the television and Jackie Robinson. Attendance began to fall off and there weren’t as many touring teams coming through—it was one of those things where baseball interest fell off. However, Jackie brought a group of All Stars one year through here and we had over 10,000 people to show up at the ballpark that day.

Danville Civil Rights Demonstrations: Securing Bail Bonds

By midsummer 1963, more than 250 Danville protesters had been arrested.

Photo: Leon Townsend,

Danville Register

During segregation, African-American funeral homes provided ambulance service for black citizens; on the evening of June 10, 1963, Mr. Peters transported injured protesters to the segregated Winslow Hospital. Before the 1963 civil rights demonstrations began, Mr. Peters attended mass meetings at various African-American churches. As demonstrations got under way, he was instrumental in obtaining bond for the first 137 people arrested, according to his testimony in Danville Corporation Court. [See Related Resources for Mr. Peters’s testimony.]

The first demonstration that took place [May 31, 1963] came after a discussion had been made between the ministers that they were going to wait until arbitration was talked about and done. Instead of that taking place, a Reverend Dunlap had a bunch of kids I’d say were fifteen to eighteen, somewhere in that neighborhood. They met at the corner of Spring and Union streets. From there they went to the Municipal Building and had a prayer.

It just so happened that day I was in lawyer [Andrew] Muse’s office, which was over the First State Bank building. Lawyer Muse had become very alarmed about the demonstration taking off without the whole council saying okay. He got on the telephone and talked to Bobby Kennedy. I scratched my head to the point that, if he thought it was that serious that he could talk to the Kennedys, and they were listening to him, then I better get busy and try to do something that I could do.

That afternoon, while I was in his office, I called families around town that I had knowledge of and worked with. We raised a little over $150,000 of interest as far as bail bonds could possibly be, because we knew that they were coming up. Eventually we ended up with people putting their property forward, almost a half-million dollars worth. All put their money for bail bond. … This was back in … early May. In fact the first two times that the demonstrations took place, the newspapers didn’t even make any note of it. There was nothing in the newspaper about it, so folks that were uptown didn’t know anything about this happening downtown. …

I was almost the [bonding] committee for a long period of time [Laughs] until I got knots in my stomach just from this anxiety of what this was all about. At that time we had a clerk of the court who was, I’m going to have to say, liberal by those standards. He and a couple of his co-workers would stay there in the evening to let us bail out folks. One night we stayed down there until about 2 o’clock, just bailing—. Then we would go home at 1 or 2 o’clock, or 12 o’clock, whatever. My telephone would start ringing for somebody who would want to get their child out or their mama out or somebody else out and then that would go on for a period of time.

James W. Peters, Jr., interviews by Emma C. Edmunds, October 11, 2003, and November 15, 2003, transcripts, Danville Community College, Danville Public Library, and Mary Blount Library at Averett University, Danville, Virginia.

Click on the image thumbnails below to view a larger version of the image.

First State Bank, Founding Directors (1919).

First State Bank was founded as the Savings Bank of Danville in 1919 under the leadership of the Reverend Samuel Moses, pastor of High Street Baptist Church, who sold $10,000 in stock to 200 original stockholders. The founding directors included, left to right, first row: J. E. Geary, F. A. Graves, W. H. Wilson, John H. Adams, E. G. Adams; second row: A. L. Winslow, G. W. Goode, P. H. Doswell, Watkin Thompson, president, S. C. Bullock, M. C. Martin; third row: A. Jamerson, Walter Beavers, Theo Manuel, J. A. Younger, L. H. Brooks, R. O. Martin.

Courtesy of Nannie G. Armstrong. Danville, Virginia.

Holbrook-Ross Neighborhood: 220 Ross Street.

George Chaney, the maternal grandfather of James Peters, Jr., owned this two-story house at Ross Street. He recalls the sense of community in the Holbrook-Ross neighborhood, and marvels at the work ethic and frugality of Mr. Chaney. The house was built around 1890, one of fourteen dwellings on Ross Street constructed at that time, according to the National Register of Historic Places registration form.

Image from photograph. Emma C. Edmunds. 2005.

Charles K. Coleman: Candidate for City Council (1946).

Charles Kenneth Coleman ran for Danville City Council in 1946, the first African-American to seek elected office since Reconstruction. He led in the third ward, where blacks cast the heaviest vote; he garnered 956 total votes, finishing tenth in a field of ten candidates. When he ran in 1948, he won 1055 votes, finishing last in a field of nine. [Read Coleman's “Candidate for City Council” ad.]

Political advertisement, Danville Commercial Appeal. April 21, 1946, page 7.

L. H. Brooks & Bro. Funeral Directors (1948).

L. H. Brooks & Bro. Funeral Directors was first located on the lower end of Patton Street, on a block of African-American businesses (a poolroom, barbershop, beauty shop, and restaurant). In 1948, the business moved to this two-story, 12,000-square-foot structure built for Mr. Peters’s father, James Peters, Sr., at 221 South Main Street in Danville; it has a stone foundation and copper roof. The Peters family moved to living quarters on the second floor (eight rooms and two baths) in April 1948, conducting business on the first floor.

Image from photograph. Emma C. Edmunds. 2005.

Arrested Danville Protester (1963).

The Danville civil rights demonstrations got under way on May 31, 1963, several weeks after Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr.,’s well-publicized protests in Birmingham, Alabama. White authorities employed tough legal stratagems against Danville demonstrators, issuing injunctions and ordinances limiting the scope of protests and requiring permits to parade. By mid-July, at least 250 protesters had been arrested, many of them seasonal tobacco workers and young people, including high school students.

Leon Townsend, Danville Register. 1963.

City Of Danville, Virginia, Etc., Versus Lawrence George Campbell, Et Als.

In his Danville Corporation Court testimony, James W. Peters, Jr., describes his May 1963 attendance at mass meetings and his role in the bail bonding effort that summer for arrested protesters. Mr. Peters tells how he answered a call for an ambulance on the evening of June 10, 1963, when a prayer vigil conducted by civil rights activists met with police violence; he picked up four victims at the corner of Loyal and Court streets and took the injured to the segregated Winslow Hospital. In the 1940s, ’50s, and ’60s, African-American funeral homes provided ambulance service to black citizens.

1963 Danville (Va.) Civil Rights Case Files. Testimony. Box 6. [view .PDF version]

James W. Peters, Jr., is the owner of L. H. Brooks & Bro. Funeral Directors, founded by his family in 1910. He was born in New York City, but moved to Danville in 1930 when his father returned to protect his interest in the funeral home, which he had helped finance. James W. Peters, Jr., attended Danville schools through the tenth grade; the Mary Potter High School in Oxford, N.C., for the eleventh and twelfth grades; and North Carolina Central and Shaw universities for two years. Mr. Peters became a funeral director in 1954 and was active in civic and social affairs. His father built Peters Park in Danville in 1948 for African-American baseball competitions and financed the payroll for the Danville All Stars, an African–American team, in the late ’40s. The younger Mr. Peters helped organize bonding efforts for protesters arrested during the 1963 demonstrations in Danville.