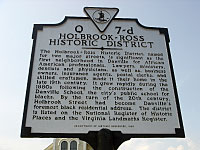

Ruth W. Isley

Teacher (1920–2008)

In her early years as a teacher, Ruth W. Isley, above far left, carried on the work of Charles K. Coleman, below.

Photos: Courtesy of Ruth W. Isley and Danville Commercial Appeal

One educator who was particularly important to Mrs. Isley was Charles Kenneth Coleman, a Howard University graduate. He taught her history at Westmoreland High School in the 1930s, including in his account the centuries-old struggles of American Americans for full citizenship. “One of the things he appealed to us and taught us was pride in black history, which was not popular then. It was not in the textbook,” said Mrs. Isley. “He knew a lot about it and taught it to us and made us feel proud.” In 1946, Charles K. Coleman, then president of the local National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the Danville Voters League, made history himself, when he ran for Danville City Council, the first African American to seek local office since 1882.

But in an interview, Mrs. Isley recalled not Charles Coleman’s significance as a political activist but his importance to her as an educator.

“I taught history when I first finished college in North Carolina and I carried right on with [Charles Kenneth Coleman’s] work with my students. He was in the modern age. He was before his time as far as his instruction was concerned.”

—Ruth W. Isley

- Interview Excerpts

- Related Resources

- Biography

These selections come from oral histories of Mrs. Isley conducted by Emma C. Edmunds in Danville, Virginia, on September 13, 2003, and November 13, 2003.

Ruth W. Isley and Nannie G. Armstrong, both longtime residents of the Holbrook-Ross neighborhood, met with Emma Edmunds on September 13, 2003, at the request of James Hughes, Jr., who runs Cunningham & Hughes Funeral Home at 351 Holbrook Street; the women, he believed, would have more memories of the Holbrook-Ross neighborhood than he. During the interview, Mrs. Isley and Mrs. Armstrong were seated in the front parlor of the funeral home; hence, Mrs. Isley’s reference to the neighborhood as “here.”

The second interview with Mrs. Isley took place in her home at 541 Holbrook Street. Mrs. Isley grew up on Aiken Street; her mother later moved to 444 Holbrook Street, a house no longer standing. When Holbrook Street was redeveloped in the 1960s, Mrs. Isley, her husband, and her mother moved to 541, one of the newer homes.

A Historic African-American Neighborhood:

Holbrook-Ross

The segregated Holbrook-Ross neighborhood was the location of African-American schools, businesses, churches, and homes.

Photo: Laurie Ripper

Also there was a private Presbyterian school down the street there, where the brick house is next to the [Presbyterian] church. It was the only black private school in Danville. It was sponsored by the Presbyterian board. … They accommodated—well, city children could come. They paid a small tuition. I think it was something like twenty-five cents a week.

Where Cleveland Street is now, that was the end of the city limits. There were many houses—all that’s changed—many houses back up on the hill and on up where black families lived. Those children had no provisions for school. The county did not make any provisions. So many children, whose parents had that money, were sent to the Presbyterian school until [the city] incorporated them, and then they could go to Westmoreland, which was a city school down the street. Westmoreland is the oldest black public school in Danville—not on the site where it is now—but it is the oldest black public school. Of course, now it’s not really Westmoreland. It’s Westmoreland Preschool. … But the buildings are still there. The last buildings are still there.

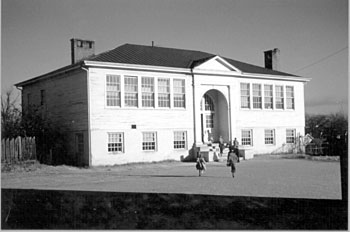

African-American Education: Westmoreland School

Westmoreland Annex was part of an educational complex that anchored the northern end of the Holbook-Ross neighborhood.

Photo: Courtesy of Cleophia Fitzgerald

The weather was much colder than it is now and we’d be bundled up in gloves and all those other things. However, we didn’t think about it, because we didn’t know anything else but the walk here and back. A lot of times the coldest corner in the United States was right up there at the corner of Holbrook and Main Street because you were facing the river wind all the way down to Westmoreland. By the time we got to school a lot of mornings, our hands were cold plus they did not close school for snow. We put on those little boots and galoshes and came on to school.

But I have no regrets. All of my family struggled a lot, and we all got a good education. All of us finished college but one, and he had the choice to go, but chose not to, but he did well with his life. We had parents who insisted that you go to school, that you do your work, you don’t play. My dad was quiet but my mama was like an army sergeant. She was. That’s the truth and we knew that. She did not fool with us and we came by her. Until she died, she was still bossy. That’s the truth. That’s right. You know that.

With the type of life we lived—. We were far from rich by any means, because all of us started to go to work when we turned teenage, 12 or 13 years old. We worked for families up in the neighborhood where we used to live. There were a lot of people that wanted somebody to sweep their porch or do something like that and that’s what we did—babysit. My brothers drove trucks for the grocery stores up there.

We learned how to fend for ourselves very young. There’s only three of us out of six living now, but I had one brother who was a college professor. I had a sister who was a college professor. One of my brothers worked in the government. I’m a teacher—I was. The one who did not see fit to go to college, he was very talented, just as smart as he could be. He liked to work in hotel work and his last job was as a skycap for Eastern Airlines in Miami. So that’s the way it went.

The Holbrook-Ross Neighborhood: A Cross-section of Classes

John Edward Geary lived at 307 Holbrook Street in the 1940s and practiced dentistry at 320 Union Street.

Photo: Emma C. Edmunds

One house just below the cemetery was the Turner family. He had a trucking business. Next door to that was the Taylor family, and Professor I. W. Taylor was a principal of Westmoreland School. Across the street on the other side was the Broadnax family. Mr. Broadnax had a store down on what used to be Union Street, but now it’s called Memorial Drive. Then there was Mrs. S. D. Boyd. She was one of the first lady black principals. Dr. Geary [a dentist], you talked with his daughter. They lived on the left-hand side of the street.

The Cunninghams, who owned Cunningham & Hughes Funeral Home, their home was there but they didn’t have the funeral home then. It’s there now. And Dr. Winslow, one of our oldest doctors, and his daughter, Mrs. Katherine Winslow, married another doctor, Dr. Clyde Luck, and they lived there. And further down on the same side was the parsonage for the Presbyterian church, in which several ministers lived, and the church was on the corner.

After you cross John Street on the left side, was a family of Allens … the one that lived on that street was a brick mason. In fact, he helped to build Holbrook Street Presbyterian Church and a lot of other things around here. He had a brother who was a famous lawyer—I can’t remember his name—up in New Jersey. That carries us on down to Westmoreland.

If you cross Gay, there was Mr. Isaac Hunt, who was a businessman. He had a store and an apartment there. Also on that side of the street coming on down to what we call Union Street, was Mrs. B. D. Coleman. She was a juvenile officer many, many years ago. Probably the only black person—I haven’t heard of one since. She had two sons who were very prominent. One of them was a lawyer in Washington, and the other one, Kenneth Coleman, graduated from Howard. He was a history teacher at Westmoreland High School when we went to high school. … And there was another store. It was the Jameson Store … right up there on the corner of Holbrook and Gay, across the corner from the church. We didn’t have lunchrooms or cafeterias, and we could go to the store and get a five-cent bun or something like that, so the kids loved that.

African-American Education: Charles Kenneth Coleman

Charles K. Coleman, who lived at 525 Holbrook Street, ran for Danville City Council in 1946.

Photo: Danville Register

He was really—he was in the modern age. He was before his time as far as his instruction was concerned. …One the things that he appealed to us and taught us, was pride in black history, which was not really that popular then. It was not in the textbook. He knew a lot about it and he taught it to us and it made us feel proud. I taught history when I first finished college in North Carolina and I carried right on with his work with my students. I was also in a class at Bennett College where we studied black history. There was another classmate of mine, we had been under him, and we did very well because we had that background and a lot of people did not have it. They just did not have it. So we appreciated that.

African-American Education: John M. Langston High School

Ruth W. Isley, first row, second from left, graduated from John M. Langston High School in 1938.

Photo: Courtesy of Ruth W. Isley

When we went into the new Langston High School, it was just like going into a millionaire building, where we had a gym, an auditorium, and a cafeteria—and also science labs and home ec labs. … We were so happy to get into a decent school, we enjoyed it. We had clubs. We did not have a band. We had physical ed and we had socials every so often. We had plays, very good plays—operettas—because we had a stage to have them on. … Mrs. [Avicia] Thorpe was my English teacher for literature, and she gave us an excellent appreciation of Shakespeare and the famous writers in that field. I also had another teacher, an English teacher. She taught grammar. They gave us an excellent background. Mr. Coleman, as I mentioned, and there were some more I can’t quite get my hands around this minute.

African-American Education: Industrial High School (The Presbyterian School)

Holbrook Street Presbyterian Church, 355 Holbrook Street, was built in 1910.

Photo: Emma C. Edmunds

“Under the pastoral leadership of Reverend Eggleston, who followed Reverend Hoskins, the Industrial High School was established in 1885. This school, better known as the Holbrook Street Presbyterian School, provided basic and Christian education for colored pupils of all denominations. Its influence was felt [far] from the church, not only in the immediate environs of Danville, but its arm was extended into Pittsylvania County and nearby North Carolina. The early classes were held in the church building during the construction of the school’s two-story brick edifice. The school was erected on the site where the current manse now stands. …

“Professor Thomas A. Long of Biddle University, now Johnson C. Smith, whose name became a household word, served as the first principal. … Many carpenters and bricklayers who were members of the church gave tirelessly of their time, labor, and talent. Mr. Robert Allen designed and oversaw the construction of this building. … Reverend Carr, who served the congregation and school from 1891 until his death in 1926, became superintendent of the Industrial High School in 1914. Professor John L. Page also served as principal. On the faculty were Mrs. W. E. Carr, Mrs. Annie Gunn, Mrs. Nanny Johnson, Miss Lucinda Yancey, Mrs. Sarah Johnson, Miss Daisy Williams [Mrs. Isley’s aunt] … and Miss Pearle E. Slade. …

“Commencement exercises for primary, intermediate, and grammar grades were held at the Ridge Street Tabernacle. Graduation for high school was held in the Industrial High School hall. Admission increased to fifteen cents. During the school year 1922–23, the twelfth grade was added, under the continued leadership of Reverend Carr. Further records indicate that [in] the academic year 1924–25, Reverend Carr acted as superintendent and Mr. Robert Hairston as principal.

“After the passing of Reverend Dr. Carr, Reverend T. B. Hargraves became pastor in 1926 and served until 1929. From 1929 to 1930, Reverend Hargraves served as the school’s superintendent, and Professor Monica G. Bullock was principal. High school graduation was held in the school auditorium. By this time the admission price had increased to twenty-five cents. Also, although fire destroyed the school in 1929, the great legacy continued throughout the remaining decades of the past century and into the twenty-first. Many of the older influential pastors and teachers in Pittsylvania County and neighboring North Carolina received their education from the instruction and guidance of the dedicated teachers of this great Presbyterian school.”

Ruth W. Isley, interview by Emma C. Edmunds, September 13, 2003, and November 13, 2003, transcripts, Danville Community College, Danville Public Library, and Mary Blount Library at Averett University, Danville, Virginia.

Click on the image thumbnails below to view a larger version of the image.

John M. Langston High School, Class of 1938.

Construction began in 1935 on John M. Langston High School, located at the corner of Gay and Holbrook streets. The new school, which opened in 1936 with E. A. Gibson as principal, generated pride in the black community for its improved facilities and its leadership. The first class graduated in 1937; Mrs. Isley was a member of the second graduating class in 1938. She is pictured, first row, second from the left.

Courtesy of Ruth W. Isley. Danville, Virginia.

Danville and Pittsylvania County Teachers. 1940s.

These Danville and Pittsylvania County teachers apparently had gathered for a summer training institute led by a male instructor from Virginia State College (University), first row, center. Luther P. Jackson, a professor at Virginia State from 1922 to 1950, believed that “classrooms would provide the space in which notions of racial equality could be fostered,” according to his biographer, Michael Dennis, and that “teachers’ organizations could become the conduits for transmitting the message of change through political education.” [Michael Dennis, Luther P. Jackson and a Life for Civil Rights, p. 10.]

Courtesy of Ruth W. Isley. Danville, Virginia.

Charles Kenneth Coleman. 1948.

On January 29, 1948, a picture of C.K. Coleman appeared on the “Colored News” page of the Danville Commercial Appeal, announcing that Coleman, a former teacher, would replace Mrs. Fiocella Motley “as colored news reporter for the Commercial Appeal, effective next Monday. Coleman will also serve as circulation manager for the colored carrier boys,” the paper said. The 1948 Danville City Directory lists Charles K. Coleman, grocer; his wife, Margaret; and Vetie B. Coleman as residents of 525 Holbrook Street.

Scan from the Danville Commercial Appeal.

Faculty Members. 1954–55.

Ruth W. Isley documented every aspect of her educational experience, arranging school photos in scrapbooks and embellishing them with her careful calligraphy. These women and men were Danville elementary school teachers in 1954–55, when the Brown v. Board of Education decision by the U.S. Supreme Court declared separate educational facilities for blacks and whites illegal. Pictured are Ruth Isley, far left, Hazel Slaughter, Gwendolyn Smith, Lillian Brent, C. Pittman Banks, Louise Harris, Ida Taylor, and Aretha Crews.

Courtesy of Ruth W. Isley. Danville, Virginia.

Westmoreland Library. 1954–55.

An effort to organize a student council at Westmoreland School drew educators from around the city; back row, from left, John Byrd, principal, Langston High School; Thomas Shavers, principal, Taylor Elementary School; N.K. Wright, teacher, Langston; James Slade, principal, Westmoreland; David Crews, principal, Grasty Elementary; front row, from left, Gwendolyn Smith; Carol Daniels; Evelyn D. Geary; Calvin Stroud; Sherryll Isley (Venable), Ruth Isley’s daughter; and an unidentified person. The Westmoreland School was located on the northern end of Holbrook Street, part of an educational complex that had anchored the neighborhood since 1881, when the Danville School was constructed there.

Courtesy of Ruth W. Isley. Danville, Virginia.

Danville educator Ruth W. Isley (1920–2008) had lifelong associations with the Holbrook-Ross neighborhood. She attended Westmoreland School and John M. Langston High School on Holbrook Street before she enrolled at Bennett College in Greensboro and received her degree. Baptized at Holbrook Street Presbyterian Church, she served there as an elder, deacon, Sunday school teacher, and musician, among other roles. As a youngster, she lived on Washington Street off West Main, but knew the neighborhood well as the center of her religious and educational life. “I really know Holbrook Street as well as I did home,” she said. In the 1950s, her parents bought a house at 444 Holbrook Street, and when the area was redeveloped in the 1960s, she and her husband and mother moved to a new brick house at 541 Holbrook. Mrs. Isley died February 3, 2008; she is buried at Oak Hill Cemetery in Danville.

Postscript

From left, Avicia H. Thorpe, Emma C. Edmunds, and Ruth H. Isley, at the Don’t Grieve After Me exhibit on African-American history, Danville Museum of Fine Arts and History, 2004.

Photo: Lawrence M. Clark

<

<