James Ulysses Griffin Hughes

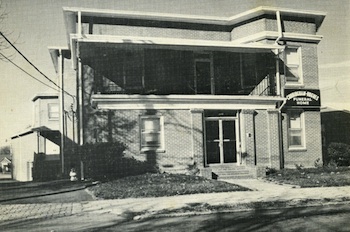

Cunningham & Hughes Funeral Home, Inc.

(b. 1948)

James Hughes’s mother, Mabel Hughes, posted 351 Holbrook Street, above (in 1974), as surety for the release of forty-four jailed civil rights protesters.

Photo: Courtesy of James U. G. Hughes

An affable man who did not participate in the demonstrations, Mr. Hughes prefers not to discuss the civil rights movement or to dwell on racial conflict. He is more passionate in describing a breakthrough of his own: the half-dozen years when he wasn’t in the funeral home business. From 1968 to 1972, he was a member of the crew of Wendell Scott, a Danville native and African American who broke into the white world of stock car racing. “Scott had it all, nerves and skill,” Mr. Hughes said with admiration. He is circumspect when asked about his mother’s bail bonding efforts, except to note parenthetically that the Holbrook-Ross neighborhood was a place where adults looked out for the welfare of young people, no matter what the circumstances.

“Everybody did a wonderful job of helping raise their children and other children, too. … ‘It takes a whole village to raise a child.’ That’s the way it was when we were coming up.”

—James U. G. Hughes

- Interview Excerpts

- Related Resources

- Biography

These selections come from an oral history of James U. G. Hughes conducted by Emma C. Edmunds on August 6, 2003, in Danville, Virginia. For one portion of the interview, Mr. Hughes’ wife, Diane, was present and participated.

Cunningham & Hughes Funeral Home, Inc.: The Family Business

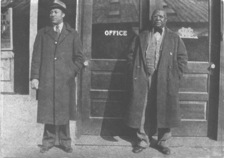

Ulysses S. Cunningham, right, and son-in-law, James G. Hughes, outside the family funeral business on Spring Street.

Photo: Courtesy of James U. G. Hughes

Ulysses Simpson Cunningham (d. 1939) and Levi Holbrook organized Holbrook & Cunningham Funeral Home on Union Street in Danville in 1898. After the death of Mr. Holbrook in 1907, U. S. and Mabel Cunningham bought his stock and changed the name to U. S. Cunningham. The funeral home moved to Spring Street around 1925, and remained there until destroyed by fire in 1948. In 1900 U. S. Cunningham built a home at 351 Holbrook Street, later the location of the funeral business.

He [Ulysses Cunningham] started in the funeral home business two years before he built the home here. The first name was Cunningham & Hughes. They had a fire in 1948 and decided to bring the funeral home up to the main home on 351 Holbrook. That’s where we are today. And that’s when I was born, in 1948. Why the fire? I don’t know. I’ve heard many, many tales about it and all like that, but I would not like to say right offhand what caused it or anything like that. But we’ve had—Well I’ll leave that alone too.

Diane Hughes recalls how Cunningham & Hughes, in the evening, was a gathering spot for African Americans as well as a funeral home. She speaks in the section below.

It was like most funeral homes in the black community then. It was the center of entertainment, should we say, in that the gentlemen would come by the funeral home in the evenings while they were washing cars, and they were all sitting around telling tales, and talking about what had happened and who was doing what. At that time, every once in a while, a little jug was passed around, and everybody had a good time, just sat around and had a good time.

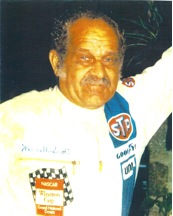

Wendell Scott: From Moonshine to Racing

Wendell Scott, above, was the first African American to break into stock car racing.

Photo: Courtesy of

Wendell Scott family

In the 1940s, James U. G. Hughes’s family operated their funeral home on Spring Street, where many black businesses were located. On the same street, Wendell Scott operated a taxi and an auto garage, running bootleg whiskey by night. Later Scott parlayed his speed and skill at beating white authorities on the moonshine circuit to become the first African American to break into white-dominated stock car racing. In 1963, the year civil rights demonstrations erupted in Danville, Scott overcame white drivers to finish first at the Grand National race in Jacksonville, Florida. Though he beat his competitors, white officials did not throw the checkered flag down until a white driver, Buck Baker, crossed the finish line. They awarded Baker the official trophy, only to be forced to recant later, giving Scott a lesser token with no inscription. In the passage below, Mr. Hughes reflects on how the lives of the Scott family and those of the Cunningham and Hughes families intersected.

Wendell used to work on our cars when they were down on Spring Street. When my grandfather and my father were down on Spring Street, he used to be our mechanic. He worked on the hearses and the cars. Scott was a cab driver, I would say, a cab driver by trade, but he did a lot of moonlighting. It was after he came back from the war, his first jobs that he had, basically, when he couldn’t find any work after coming back from the service. So he decided he would become a cab driver. From there he started tinkering around with cars, keeping ours up like a mechanic would do. … I know of about two or three cars that we used to own that we gave to him before he passed away. In fact, they talk about a Cadillac that he used to drive to the racetrack, which used to be ours. … When he started into the Grand National, it was very, very expensive, and from time to time they [Mr. Hughes’s family] would help him with some funds, to kind of tide him over and help him out. I would say [that was] probably in the 1950s and ’60s.

First State Bank: James G. Hughes

James G. Hughes worked at First State Bank from 1928 to 1933.

Photo: Courtesy of James U. G. Hughes

After completing studies at Virginia Union University, James U. G. Hughes’s father, James G. Hughes (1902–79), moved to Danville and worked at First State Bank from 1928 to 1933. He married Mabel Irene Cunningham (1909–96) in 1931, and, two years later, became a partner in Cunningham & Hughes Funeral Home. James G. Hughes served on the boards of the Broadnax YMCA and First State Bank and was active in the Elks Lodge and the Blanks Club.

My father graduated from school in accounting and business administration, so he knew one of the gentlemen there at First State Bank. And [the gentleman] got him to come [to First State] and from there he became a teller, whatever you want to call it. Being at the bank, he got a chance to meet a whole lot of people from around the area, and that’s how he met—Well, he knew my mother when they were in school and they became even closer and got married in 1932. A lot of people dealt at First State Bank because of his personality—the way he was and the way he carried himself. The bank became one of the strongest banks in the Danville area in that era.

The Holbrook-Ross Neighborhood: “A Village to Raise a Child”

Students cross Holbrook Street near John M. Langston High School and Westmoreland Elementary School.

Photo: Danville Chamber of Commerce

Mr. Hughes remembers the sense of community that characterized the Holbrook-Ross neighborhood in the years when he was growing up. In his view, the churches—Loyal Baptist, Holbrook Street Presbyterian, and Calvary Baptist—were the most important institutions in the neighborhood. He also reiterated a point made in other interviews: teachers at the segregated John M. Langston High School not only conveyed information about their subjects but also lessons about life.

The church I belong to now, Holbrook Street Presbyterian Church, had the largest Sunday school, and also had the largest youth Sunday school in the area. The people were kind, and they were more like kinfolk than neighbors or people that you didn’t know, really. And everybody got along and did a wonderful job of helping raise their children and other children, too. Mrs. [Hillary] Clinton made a statement some time ago, “It takes a whole village to raise a child,” and that’s the way it was when we were coming up. Everybody on the street was our mother and our father. We couldn’t do wrong. …

I think that people in that era all had children at heart and in mind. No one really did anything that was wrong [without knowing that] by the time you got home, you would get yourself spanked. … [I]t was not any difference in what area that you would go to. [There] was always a mother there looking. … As far as hanging out, we all hung out at school, at the corner stores, at the churches, and here at the [funeral home] business. … We used to play football in the street, and baseball in the street. We had a swimming pool in the back [of the funeral home], and normally sat around and talked and had ourselves a good time.

I went to John M. Langston High School for four years. … All of the teachers in the school when we were at Langston were good in their fields. They all taught, not only what their fields were—as far as English and math and all—but they also taught us about life and how to get along with people. And this is something that we’re missing in the school system today.

Holbrook Street Presbyterian: Sunday School

Holbrook Street Presbyterian Church, detail above, provided a welcoming place for youth.

Photo: Emma C. Edmunds

Mr. Hughes reflects on the way the Holbrook Street Presbyterian Church, under the leadership of the Reverend Walter Anderson, involved the young people of the community. According to Mr. Hughes, as many as 150 children—including youth from Loyal Baptist and Calvary Baptist churches on Holbrook Street—attended Sunday school at Holbrook Street Presbyterian in the 1950s. Well-known throughout the community and by black and white ministers, Rev. Anderson of Holbrook Street Presbyterian served as a positive role model for young people.

I joined Holbrook Street Presbyterian Church when I was about fourteen, fifteen years old. I was in the seventh grade. Personally, the preacher who was there could not preach his way out of a paper bag. But once he left the pulpit, he did everything that the Book says. That’s how good he was. He and his wife never had any children, but there was never a day that went by that there weren’t some children there at the house. … On Christmas we had the Nativity scene. We had teachers from our school that were members of the church that had us do different things over the years. Easter, whatever holiday it was, the young people had a program. [There] was always an adult teacher from the school there to help us.

What it did for me? I would say that it did a whole lot. In studying with the minister—because I knew him and he lived next door—a lot of things that he would say I would listen to and come back and check the Bible to make sure that what he was saying was correct. He was correct in the things that he said, and things that he did. He played a big impact in my life and others, too. … [H]e was named Walter Anderson. All in all, he was a real good, nice man that no one could say anything negative about. Even today if you would go and talk to some of the people in the street that knew of him, there wasn’t anything negative. Back then we didn’t have a lot of negative role models. We had a lot of positive role models that keep us in line and keep us straight like we should be. There were a lot of positive people that were around, not only in this community, but in other communities, and they would help young people and widows and everybody else.

The World of Work: Cunningham & Hughes to Wendell Scott

James U. G. Hughes was a member of the crew of Wendell Scott, above, for six years.

Photo: Courtesy of

Wendell Scott family

Mr. Hughes’s first job, at twelve to fifteen years of age, was working at the funeral home, washing cars. He was later employed at Danville radio stations WILA for six years, and WBTM for two years. Through his family’s friendship with Wendell Scott, he became a member of the driver’s crew in 1966, working with him for about six years, gassing the car, cleaning windows, and fixing tires. Mr. Hughes loved the sport, and found in Scott a racer of courage and skill.

In an informal conversation after his taped interview, he acknowledges the disapproving white crowds that often greeted their entourage and recalls how tension sometimes split the air. He voices deep regret, too, that the white imprimatur of success—a corporate sponsorship—always eluded his hero. “Scott had it all, nerves and skill,” he said. “I always hoped a company would take a chance on him, but he never got a corporate sponsorship.” In this taped excerpt, he recalls how he started working for Scott.

I worked six years, six and a half years, in the pit with Wendell Scott racing on Sundays. That was from Maine to Florida to California. It was a fun time. I learned how to be a mechanic, and I learned a lot about life. … They’ve always said that Wendell was some kin to us and my mother and my father used to help him out as far as money was concerned, as far as going different places. … I decided to go to Martinsville Motor Speedway one Sunday, just to see what all that noise was that I heard so much about, and I got hooked. I’m not that much of a racing fan now as I used to [be], I guess, because my ears are just about gone from the car noise and also from the radio station, but I still like to see it. It’s still interesting to know the ins and outs, the shortcuts that the fellows take from race to race.

Click on the image thumbnails below to view a larger version of the images.

MABEL IRENE CUNNINGHAM HUGHES (1909–96).

Mabel Irene Cunningham Hughes, the mother of James U. G. Hughes, was born at 351 Holbrook Street in Danville. She attended Holbrook Street Presbyterian School and Hampton University, graduating from Virginia Union College in Richmond. Before joining her family’s funeral business, Mrs. Hughes taught in the local public schools. She and her husband, James G. Hughes, had two children, James U. G. Hughes and Thomas Hughes, who died in infancy. “Though she was blessed with two children,” said the program for her funeral, “her home was also the home of her adopted children, Connie, Mabel, ‘Jack Frost’ and Thurman and many others.”

Image scan from funeral program. Courtesy of James U. G. Hughes. Danville, Virginia.

DANVILLE CIVIL RIGHTS Bonding (JUNE 10, 1963).

Mabel Hughes posted 351 Holbrook Street, valued at $40,000, as surety for the release of fourty-four civil rights protesters arrested on June 10, 1963. Of those, at least nineteen were high school students, including Ezell Barksdale; Irvin Christopher Bethel; Everett Bruce, Jr.; Barbara Cardwell; David Lea Davis; Ellis Dodson; Thurman Echols; Gladys Virginia Giles; Robert Lewis; William Lipscomb; Margie Mabin; Charlie Mason; Marilyn Morton; Archie Petty; William Howard Scott; Michael Smith; Vernice Smith; Ralph Walters; and Melvin Warner. She also provided bond for the Reverend Hildreth G. McGhee, who led the peaceful prayer vigil that met with police violence and fire hoses. [Source: 1963 Danville (Va.) Civil Rights Case Files.]

Photograph. Courtesy of James U. G. Hughes. Danville, Virginia. 1974.

DANVILLE CIVIL RIGHTS PROTESTS (JUNE 10, 1963).

As a youngster, Thurman O. Echols, pictured here, lived with his family in an apartment on Roberts Street in the Holbrook-Ross neighborhood. He became acquainted with Mabel and James Hughes because he passed the funeral home every day going to school and lived with the couple from 1964 to 1970. While Mrs. Hughes provided bond to get him out of jail after his arrest on June 10, 1963, left; her husband gave him financial help and encouragement to attend and graduate from Virginia Union University. “He probably has had a greater influence on my life than anybody—other than my own father,” said Rev. Echols, now pastor of Moral Hill Baptist Church in Axton, Virginia.

Photograph. Courtesy of the Library of Virginia. 1963.

WENDELL OLIVER SCOTT (1921–90)¸ DANVILLE STOCK CAR RACE DRIVER.

Wendell Scott learned to be a mechanic in the U.S. Army in World War II and returned to Danville to open Scott’s Garage on Spring Street in 1947. He drove a taxi and was a mechanic by day, and he sometimes ran moonshine at night. His parlayed his skill as a mechanic and driver into race car driving, competing initially on dirt tracks in Virginia and North Carolina. Issued his NASCAR license in the early 1950s, he competed in 495 Grand National and Winston Cup events over thirteen seasons. His biggest victory was at a NASCAR competition on December 1, 1963, in Jacksonville, Florida; he was proclaimed the winner, but the accolade came hours after the race concluded and white driver Buck Baker had celebrated in the victory circle. He retired from NASCAR in 1973 after injuries sustained in a crash at Talladega, Alabama. He died of spinal cancer in 1990. [Source: “Legends of NASCAR” Web site.]

Scan of a photograph. Courtesy of the family of Wendell Scott.

JAMES U. G. HUGHES AND HIS FAMILY ARE LONGTIME OWNERS AND OPERATORS of Cunningham & Hughes Funeral Home, Inc., on Holbrook Street in Danville. His family lived on the second floor of 351 Holbrook Street, with Cunningham & Hughes located downstairs. His first job, at twelve to fifteen years of age, was working at the funeral home, washing cars. Mr. Hughes, who attended Westmoreland Elementary School and John M. Langston High School, worked at Danville radio station WILA for six years, and WBTM for two years. Through his family’s friendship with Wendell Scott, he became a member of the African-American driver’s crew, working on Sundays from 1966 to 1972, gassing the car, cleaning windows, and fixing tires. In 1972 he married Diane Coleman and became a funeral director with Cunningham & Hughes.