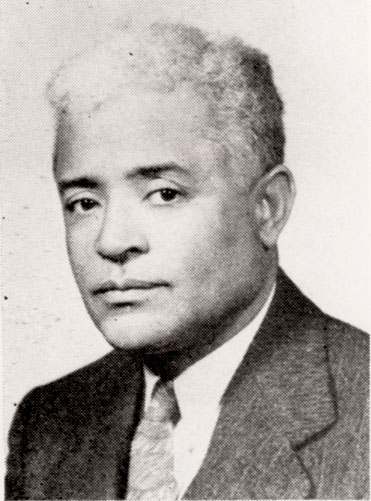

Dorothy O. Harris

Teacher and Principal (b. 1930)

Dorothy Harris joined the local civil rights movement after seeing fire hoses directed at demonstrators.

Photo: Leon Townsend,

Danville Register

Mrs. Harris volunteered to work at High Street Baptist Church, a center for the local movement. There she was a recording secretary, noting who marched, who was arrested, and who was in need of bail. Her husband, the late Charles Harris—then a teller at the local African-American bank—helped organize the bonding effort.

Later that summer, Mrs. Harris resumed teaching in Danville, and, in 1970, became principal of a newly integrated elementary school. Charles Harris was elected to Danville City Council in 1968 and became the city’s first African-American mayor, serving from 1980 to 1984. He died in 1988.

“If people could be out there having their life threatened to bring about a change in opportunities for our race, who was I not to be a part? I had to be a part of it. The same thing could happen to me.”

—Dorothy O. Harris

- Interview Excerpts

- Related Resources

- Biography

These selections come from oral histories of Mrs. Harris conducted by Emma C. Edmunds in Danville, Virginia, on April 4, April 11, and May 9, 2003.

Citizenship and Voting: Luther P. Jackson

Dorothy Harris studied with Luther P. Jackson when she was a student at Virginia State University.

Photo: Virginia State University

Dr. Luther P. Jackson would always tell us, “When you get out, register and vote. Own property so that you can be recognized as a true citizen. Don’t go out there depending on other people to do things for you. If you register and vote and own property, people will listen to you.” That was a lesson he taught in his class to all of his students. And of course, my parents believed in voting too.

We used to have a group from the University of Virginia that would come to our school. See there were professors in sociology and all that were trying to advance race relations even at that time. We would have meetings at Virginia State one month and then we would go up to Charlottesville to have a meeting. You know, it was just something that was happening. No big thing, but they were promoting this togetherness of the races in our generation. … Dr. Harold B. Roberts was in sociology and he was very much into that type of thing. And a Dr. Davies. It was through the student organizations that this happened, but it did. And then we would go out to lunch after that.

For further information, see “Virginia State University,” here, an entry in the African American Heritage online publication of the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities.

Segregation: Danville Municipal Court

Seating in the courtroom of the Danville Municipal Courthouse, above, was segregated in the 1950s.

Photo: Emma C. Edmunds

When I taught in high school, I took my American history class down to the court to observe because the students used to say, “There is no justice in America.” And I said, “Well we can get justice in the courts.” And I said, “We’ll go down and observe one day.” I made arrangements with the clerk of court to take the class down to observe and when we got down there, I sat on the front left side of the first two rows, and the bailiff came out and he said to me, “You cannot sit here.” And I said, “Why? Really I thought anybody could sit anywhere they wanted to in the court.” And he said, “This is reserved for whites.” I said, “Well I’m sorry. This is a class in American History. We have been emphasizing justice. I cannot move.”

I got very nervous, and then the judge came out and looked. They knew me though. They knew my husband and all. And then the clerk of court came again, the bailiff came back and finally, Jerry Williams’s father went through the court. He was an attorney. I said, “Well if they arrest me, Jerry is here. I’ll get him to get me out.” But anyway, finally, they said, “Okay, this time you can sit, but your seats are supposed to be in the back of the court.” But I stayed there. Then, of course, I did not let my students know this. When we got back in the classroom, we did have a discussion on it. But I could not move them there and say, you know, “This is justice.” I would have caused them to lose all belief in America.

Segregation: Public Facilities

The signage and practice of segregation were prevalent in Danville into the 1960s.

Photo: Danville Register

I had an experience, with a co-worker, a teacher. He’s now deceased. When I was teaching at the high school, this was between 1951 and ’56, we used to take our busloads of students to Roanoke for the basketball tournament. We left with two buses that morning going, and this particular teacher, Ned Wright, had brought some sweet coffee. Up at Penhook, on Route 40, he had to stop to go to the bathroom. The bus driver went as far as he could, then he said, “I have to get off.” We got to this store that had a bathroom. He got off and went in there, and the man denied him the use of it.

He stayed off the bus a while, so another teacher and I got out to check on him. He was standing under the building and said he could not hold having to go to the bathroom, so he had messed up his clothes. That just tore us up. We had to decide what to do. We didn’t want the children to know what had happened. We told him that we would go and find a phone. The [white] man would not let us use his telephone. We had to drive up maybe about a mile to use a telephone to call his wife and let her know that he would be at this particular place. His wife was pregnant at the time, “Don’t get upset, he’s okay, but he can’t go on to Roanoke because his clothes have been messed up.” Then we called the music teacher, Percy—I can’t think of Percy’s last name—called him to come, to tell him where to get him. He came up and picked him up and carried him home.

This is what segregation would do for you. You couldn’t even find a bathroom to use when you were traveling. These were the things that really came close to your heart when you say, “Now I don’t want my children to go through this. I’ve been through this, but I don’t want them to have to go through this.” So people became committed to the movement to bring about change.

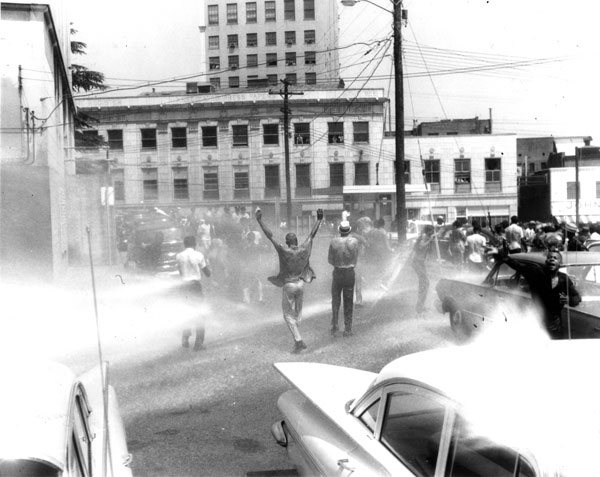

Danville Civil Rights Demonstrations: 1963 Violence

Authorities directed fire hoses at 1963 Danville demonstrators.

Photo: Danville Register

The day that I really decided to become an active part of the movement was in June, when I turned in my last report. I worked for eleven months and I was standing in the school board office, looking out at the courthouse. The policemen had water hoses pushing the demonstrators down the street, just with all of the power of the water. I said to the secretary, who was white, and she was looking with me, I said, “You know where I will be spending the rest of my summer? As a part of this movement. This is not right.” And she said, “It surely is not.”…

At that time, the ministers would meet at the church. I, along with a Mrs. Bertha Bruce, became the secretary of the movement. We kept records. We kept a record of who would be demonstrating. We kept a record of whether they would be going to jail or coming back. I didn’t interact that much directly with the demonstrators. I was there, but I was involved in other administrative responsibilities to set up the movement and to have accountability of what was going on.

Women did most of the secretarial work that was a requirement for the movement. They served as secretaries for the administrative staff—secretaries to get programs printed. They also provided food for those who were demonstrating. They cooked it at the church. Other people brought food in and it was more in a, I guess, a service capacity that women worked rather than leadership. Some of the women did demonstrate. They were arrested and stayed short times in jail. I guess that was about the extent of their involvement at that time. The men took more leadership in policy making and decision making, wherein the women were supportive and did the necessary paperwork for things to follow through with.

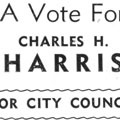

First Black Mayor And Voting: Charles H. Harris

Charles Harris, left, a First State Bank teller, was elected the first black mayor of Danville.

Photo: First State Bank

He was elected in 1980 as [Danville] mayor and served through 1984, served very well, and in ’87 the cancer came back. At that time he was in his twentieth year on council. Twentieth year. If his health had not failed, he was going to go back and I was trying to talk him out of it, but the health came in and it became a real issue. That was in the fall of ’87 and in ’88 his term would have been up, but he would have to stand for reelection in June and he died in May.

And on the 8th of May, we had an election and my third daughter was here. That morning we had to help him get up and get dressed, but he got up, got a white shirt on, his suit, and we took him down to Taylor School. He always had the practice of being the first to get down to vote. So at six o’clock, we were going down to the school. We had to lift him, more or less, up the steps to get him in to vote and he came back and he was satisfied and said to the children, “You see how important voting is.” So after that, we knew it was downhill, you know, from then on, but that was what he wanted to do. He wanted to vote. He wanted to vote and he did do that.

He did, and I did too. Like I tell you, our professor in school always told us, “Vote, own property.” It was “register, vote, and own property. Then you’ll gain respect from people.”

Whites and blacks together supported him and there were some blacks who felt that he was too much of a moderate—there were some blacks [who did]. But he could negotiate and get things done. He was not saying, “We’re going to do this as blacks,” or like that. He was negotiating behind the scenes and that’s when many opportunities came to us. He was a moderate person. Not aggressive with words, but he would get his point over. I have it here somewhere, but he carried the city with the largest number of votes I think the second time that he ran. So he proved himself as a person capable of doing things. The community recognized his ability and forgot that he was black for a while. You know, they recognized what he was able to do.

When my husband passed, this community—when I say community, I mean black and white—mourned with us. Chief Morris had cut off the lane next to our house out here because parking was a problem, for people to come and park and come down. People were coming from all categories of life, which was great support for the children. Great support for the children. The day that he was funeralized, the policemen were standing on every corner of the street, saluting him as he went by. The casket went by the city hall when we were on the way to the cemetery. I did not know was going to happen, but that was great support. We just felt that not only had we lost him, but the community had.

I told the children they have a great legacy and I want them to honor it with their lives.

Dorothy O. Harris, interviews by Emma C. Edmunds, April 4, April 11, May 9, 2003, transcripts, Danville Community College, Danville Public Library, and Mary Blount Library at Averett University, Danville, Virginia

Click on the image thumbnails below to view a larger version of the image.

Luther P. Jackson (1892–1950).

The son of former slaves, Luther P. Jackson was born in Lexington, Kentucky, in 1892. He received his bachelor’s and master’s degrees from Fisk University in Tennessee and his Ph.D. from the University of Chicago. He was a professor at Virginia State University in Petersburg from 1922 to 1950. Regarded as an “activist intellectual” he urged blacks to vote and to litigate to achieve full citizenship.

Courtesy of Virginia State University. Petersburg, Virginia.

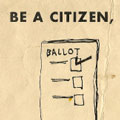

Virginia Citizens Conference Voting Rights Brochure (c. 1956–57).

Virginia was one of five states that in 1963—the year of the Danville civil rights protests—still required the payment of a poll tax as a prerequisite for voting. This 1950s brochure explains that citizens were required to pay the poll tax or capitation tax of $1.50 each December 5th. To vote in the June 8th primary or October 5th general election in 1957, the registrant must have paid all poll taxes by May 4, 1957. The U.S. Supreme Court declared Virginia’s poll tax unconstitutional in 1966.

Side two of two sides. Gift from Cleophia Fitzgerald to Emma C. Edmunds.

The Danville Municipal Building (1926–27).

The Danville Municipal Building housed in 1963 the corporation and municipal courts, the police force, and city council offices and chambers. Directly behind the Municipal Building, separated from it by a narrow alleyway, was the jail. Two flights of granite steps lead past a statue of longtime mayor Harry Wooding (1844–1938), a Confederate veteran, to three tall bronze doors. Protesters often gathered on the steps of the Municipal Building during the 1963 civil rights demonstrations.

Image from slide. Emma C. Edmunds, 1998.

High Street Baptist Church.

High Street Baptist Church was one of the centers of the 1963 Danville civil rights movement, a place where demonstrations were organized, strategy discussed, the bonding committee operated, protesters were fed, and mass meetings held. During the summer of 1963, protesters often marched from High Street Baptist Church through the black business district on Union Street, crossing Main Street, then following Union to the Municipal Building, where they sang freedom songs and demonstrated against segregation.

Image from photograph. Emma C. Edmunds. 2003.

Fire Hoses Turned on Civil Rights Protesters. 1963.

The use of fire hoses and billy clubs against black protesters helped mobilize a broad swath of African-American citizens in Danville to become involved in the 1963 protests. Dorothy O. Harris, an educator, became active as a volunteer, signing up to work at High Street Baptist Church as a recording secretary, noting who marched, who was arrested, and who was in need of bond. Charles Harris, a black banker and Mrs. Harris’s husband, was among those who went to the courthouse to make the bail bonding arrangements for those who were jailed.

Leon Townsend, Danville Register. 1963.

A Vote for Charles H. Harris for City Council. 1964 election card.

Charles H. Harris, a banker with First State Bank, ran for election to Danville City Council in 1964, but was defeated. The Danville Register on June 10, 1964, interpreted the victory of the five white male candidates as “a mammoth endorsement of the city’s handling of racial disturbances here last summer.” In a record turnout, Harris finished ninth in a twelve-man field. Four years later, he won election to council, becoming the first black to hold such an office in Danville since Reconstruction.

Election Card (3 7/8" x 2 1/4"). 1964. Gift from Dorothy O. Harris to Emma C. Edmunds. 2004.

Dorothy O. Harris is a longtime Danville educator. Her life history extends to rural roots in Mecklenburg County, Virginia where her parents lived. She was born and educated at Oak Level School and West End High School before attending Virginia State College in Petersburg, Virginia, from 1946 to 1950 for a bachelor’s degree and a master’s in 1951. She moved to Danville when her husband, Charles, took a job at First State Bank, an African-American owned and operated institution. Mrs. Harris taught history and social studies at John M. Langston High School until 1955, when her first child was born. From 1956 to 1969 she was a visiting teacher (today's school social worker) with the Danville City Schools. When the Danville City Schools integrated, she was principal of Grove Park Elementary, 1969–70; principal of Taylor Elementary School, 1983–1990.

<

<