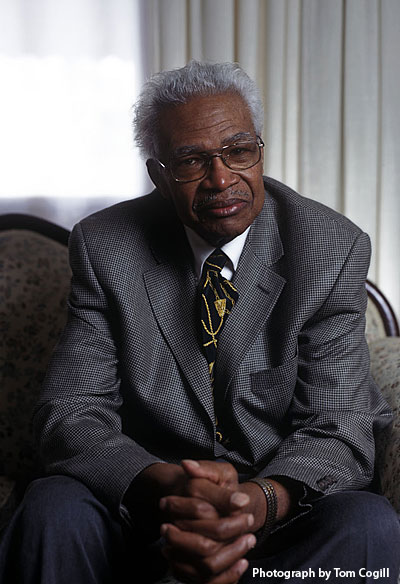

Lawrence M. Clark, Ed.D.

Professor Emeritus and

Former Associate Provost

North Carolina State University

(b. 1934)

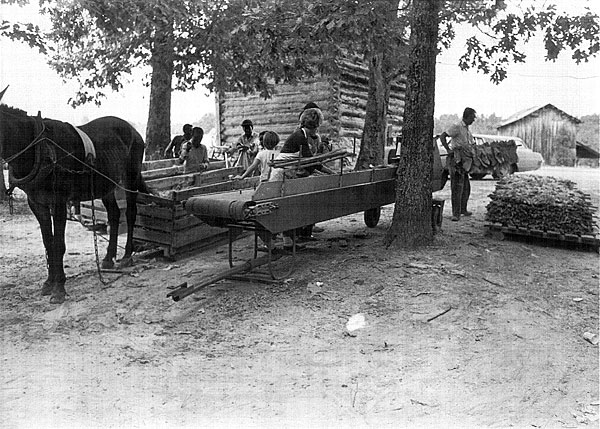

Dr. Clark’s mother, like the women above, was a seasonal tobacco worker.

Photo: Danville Chamber of Commerce

Dr. Clark’s father was a mail carrier at Dan River Mills—one of the highest-paying posts for an African American. After finishing high school, Dr. Clark also worked at Dan River, blowing cotton from the ceiling of the spinning room. The cotton would often fall and break the thread of the looms, he recalled. “The women threading those machines used to get totally upset with me. One day this woman picked up some bobbins and threw them at me. In my rage, I threw them back. I walked out of the mill, down to the military complex, and joined the Army and never looked back.”

“Growing up watching my mom and dad and watching other blacks—how they were treated in terms of servitude—gave me a sense that I never wanted that to happen to me.”

—Lawrence M. Clark

- Interview Excerpts

- Related Resources

- Biography

The selections below come from an oral history of Dr. Clark conducted by Emma C. Edmunds on October 2, 1998, at the Beacon Ridge Retreat Center about twenty miles west of Danville in rural Pittsylvania County. Dr. Clark’s grandfather lived next to and tended the land where Beacon Ridge is located; the grandson bought the fourteen-acre tract to fulfill a dream of establishing a cultural and conference center and building a family retreat.

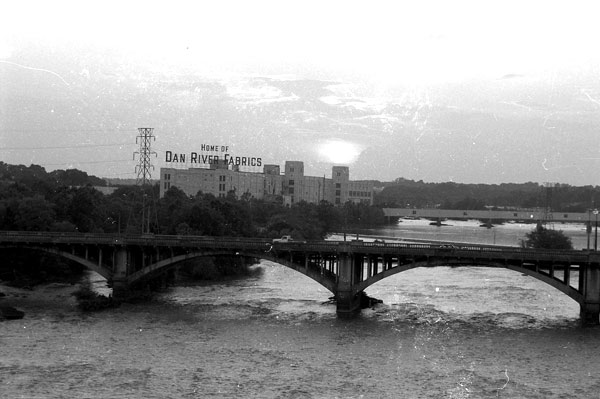

Tobacco and Textiles: Mainstays of the Danville Economy

Lawrence Clark’s father was a mail carrier at Dan River Mills, one of the largest textile operations in the South.

Photo: Leon Townsend, Danville Register

My mother worked in the tobacco factory, and we would go with her down while they [she and other black women] would beg for jobs. This was in Danville. The tobacco factory [had] seasonal jobs. … This white fellow would stand on a platform—he would hire people by picking out certain people in the crowd. The women would come from the black neighborhoods ready to work, and they would have their hands up, trying to shout and get recognized. This fellow would hire maybe three or four people every hour. You would see the people raising their hands for six hours, come at six until twelve. I’m standing there as a kid. And my mom would go every night trying to get this job. It was awful. I saw that and I said, “I hope that never happens to me.”

Growing up watching my mom and dad and watching other blacks—how they were treated in terms of servitude—gave me a sense that I never wanted that to happen to me. When I grew up and finished high school, I went into the cotton mill. My dad had the highest position for a black. He carried mail in Dan River and he wanted me to aspire for his job.

I was blowing cotton off of the ceiling in the spinning room #2. They had these open looms. My job was to get the cotton down off the ceiling. But when the cotton fell onto the looms, it would break the thread on the looms and the women in this room threading those machines and keeping up with its spinning used to get totally upset with me. It was a fire hazard. I had to blow the cotton, that was my job, but it would fall on their looms. One day this woman picked up some bobbins and threw them at me. And in my rage, I threw them back. I walked out of the mill, walked down to the military complex, and I joined the Army and never looked back.

Segregated Education: “Tough Love” from Teachers

Avicia H. Thorpe, second row, center, was a longtime, and much admired, teacher of English at John M. Langston High School; she founded the student newspaper, the Langstonian.

Photo: Courtesy of Avicia H. Thorpe

At the turn of the century, there were only four professions that African Americans could actually go into: a little law, a little theology, a little medicine, and a lot of teaching. For the most part, the black community really cherished their teachers because some fine minds were in these schools. I got caught in a love triangle when I was growing up. I was in a Christian home; I went to a school that celebrated me; I went to church. This triangle—home, school, and church with me in the middle—was in equilibrium, so well balanced. I knew that the teachers had my interest, the community had my interest, and the church had my interest. So like all communities, I had a lot of mothers. If I did wrong down the street, I had a whole lot of older women in the neighborhood that would correct me. I might get a beating down the street, and I’d get a beating when I got home.

In school, we discovered that there was a tremendous amount of tough love. If a teacher saw a student that showed some promise, then they would kind of tuck them under their shoulders and try to work with them. So when I got to high school, Mrs. Ella Ivy was my geometry teacher; and Mrs. Thorpe my English teacher; Mrs. Murphy, my counselor; and Mrs. Fannie Owens worked very hard with me.

And so as I am building a kind of museum in Danville about African Americans, I’m having the teachers that we in the community celebrate. I’m having them carved so that they will be part of our exhibit in our museum. The two right now that we have had carved that stand out would be Mrs. Thorpe and Mrs. Murphy. We have about six others that we hope to bring on line that also stand out.

Segregation: Interactions and Relationships between Blacks and Whites

African-American and white children work together on a Pittsylvania County tobacco farm.

Photo: Leon Townsend,

Danville Register

We got the word very, very clearly in a whole lot of different ways from our parents and from the community. And also [by] what was happening to us. I went to work as a nine-year-old at a grocery store near our house, picking up bottles and working. The store was owned by Straiders & Son. Straider had a daughter named Norma. He had a son working there, and the wife worked in the store. I stayed at the store working through high school. Every evening I would go to the store.

Norma was much younger than I—about three or four years—but she didn’t know very much. She was not paying close attention to her books in high school. She was flunking geometry. I had had geometry. She asked me to help her. Her brother had gone and joined the Navy by that time. I was back on the meat block in the back of the store. Norma was there. We were leaning over, and I was helping her with her homework because the store would close about 6:30 in the evening. Her mother came to me and said that she wanted me to stop tutoring Norma because it didn’t look good, my being that close to Norma in the store with the customers coming in.

I got the message very, very clearly. That was a no-no. What would happen—if someone said that you were molesting a person—your word wouldn’t be believed. You had no chance in the courts. We tried to stay away from any contact during those days. I still remember that’s very, very real because it’s etched into your psyche.

Virginia Civil Rights Demonstrations: Training in Nonviolence

Police arrest a 1963 Danville protester, who—rather than fighting arrest—responds by going limp.

Photo: Danville Register

I entered Virginia State College in 1956 in Petersburg, Virginia. As a student there, we became quite involved in the demonstrations and the marching going on from our campus to the city of Petersburg. At that time, Wyatt Tee Walker was a pastor at Gillfield Baptist Church in Petersburg, and it became the church that we would march from, and also from the campus.

Our responsibility was to try to integrate Woolworth’s and the movie theaters then in Petersburg, and also the courtrooms. So it was a nonviolent movement led by some of the townspeople and people from the campus. We all thought we were making a statement and a contribution. Flowerpots were set in front of us when we tried to order food from the—especially Woolworth’s. It was an upbeat time for us. People would get arrested. We didn’t have any violence, but it was tense. We thought we were trying to make a contribution. Dorothy Cotton, who was in the library at that time, [had] a golden voice and she would lead in singing “We Shall Overcome.” It was a very good time for us in terms of what were trying to accomplish. …

It [the civil rights movement] was in the news—Birmingham and Martin Luther King’s speeches. Here we were—college students and nothing to hide. We were not threatened. Older people would lose their jobs—so it became our duty. We got caught up in saying, “Okay, we’re students also.” As movements moved and especially with Wyatt Tee and the ministers calling on us, we were in much better shape than anyone else to make these kinds of statements. We were students, both high school and college. We had 2,500 students, I guess, at Virginia State College. I don’t totally recall how it all came about. But we did practice nonviolence, and people would come on the campus speaking and talking. Richmond wasn’t too far away. There was Virginia Union and the other schools—so we thought that perhaps Virginia State College ought to be involved. We got caught up that way. …

In the movement, you have to be very, very careful to get the hotheads out. There are people that cannot work in a nonviolent way. What we would do is go into the basements of churches and learn how to take punches and how to roll if you get attacked. How do you cover your head so you won’t get kicked in the head? How you ball up so that you don’t get kicked in the groin. We would beat up on each other—the idea of testing people to see if we could get the hotheads out. They were left behind. [Laughs.] Because in a nonviolent movement, the first blow is—the other side is waiting for that to happen. If you do that, then you lose the moral climate for what you are trying to accomplish. I’ve seen some people we knew were hotheads that we didn’t want to be around in movements like that. So all this preparation—

The other thing that happened in the movement, Martin Luther King would have branches. Wyatt Tee had a branch there [Petersburg]. You would have people that would say, “Okay, what is the economic power of this city? What companies to boycott to make the greatest impact?” These activities occurred before the demonstrations. It was well planned with all those kinds of strategies. Now what happened—students were not totally part of the strategies. But we were just sent someplace and told to do these kinds of things.

I’m sure Wyatt Tee became well known in the movement in such a way that he was invited to be the executive director [of the Southern Christian Leadership Council] for Martin Luther King. He’s still strong today and ended up being one of the ten most outstanding preachers in the nation. But it was there that he moved us and rallied us. But not everybody in the community was actually happy about this cause. Only a small fragment of the people at that time got on board. …

Editor’s Note: In another portion of his interview, below, Dr. Clark spoke about the importance of nonviolent responses and his early training in the technique.

When you’re out and someone looked like they were getting ready to use force against you, turning the other cheek became very, very important. Or even when you were arrested, not to strike back. But we had been playing those games, those defense-mechanism games, for many, many years, and we didn’t know that we were doing it. We used to call it playing the dozen. We used to tease each other. But the object of the game was that you need to take it. You lose the game if you get angry. What we would do, we’d say, “Your mother is no good. I saw your sister last night with this other man.” And we would just tease each other. But the whole idea is that if you break, then you lose the game.

For more information on Wyatt Tee Walker, see “Wyatt Tee Walker (1929– ),” here, an article contributed by Charlie Lawling to Encyclopedia Virginia, an online publication of the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities.

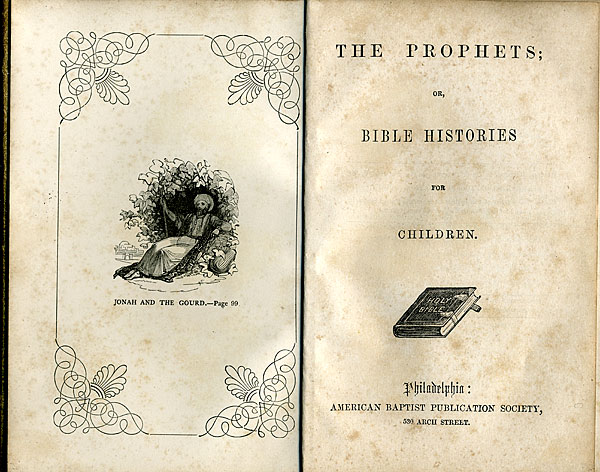

Danville African-American History: From Reconstruction to Civil Rights

This title page introduces The Prophets: Bible Histories for Children, a mid-nineteenth-century book used for the religious education of young African Americans. It is owned by Loyal Baptist Church, founded in 1870 by freed slaves.

Scan: Courtesy of Loyal Baptist Church

History is a mirror by which we see ourselves, where we’ve come from, and also it gives us an opportunity to understand where we’re going. For our children’s children, I think we ought to record things and try to analyze things to try to understand what strategies were used. What were some of the obstacles? What is going on in terms of the human spirit of brothers and sisters trying to live together on this planet? …

I would hope that we could have an African-American museum, or a section of a museum that talks about the life of African-American people, which would be a great contribution to the city and to the state. I am collecting things and trying to catalog them so that if such a thing comes about, we would have something to put in it so people could see. … We’re writing the history of education. We’re writing the history of health care and anything else that we can: marches, courtships, and family heirlooms and just people who played a tremendous part.

I really believe that if we can put these things together it will be, for me, an educational piece for all of our citizens around here to see their past in two different ways. One, through the eyes of my white colleagues, and then through the eyes of my African-American colleagues. Sometimes when you stand and look at something, you might need to open a lot of windows, because you need a total view to come to the understanding of how people see history and how people see their own experiences.

Lawrence M. Clark, Ed.D., interview by Emma C. Edmunds, October 2, 1998, transcript, Danville Community College, Danville Public Library, and Mary Blount Library at Averett University, Danville, Virginia.

Click on the image thumbnails below to view a larger version of the image.

Dan River Mills. Home of Dan River Fabrics.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, there were 6,035 persons employed in textile manufacturing in Danville in 1960, more proportionately and in aggregate than in any other city in Virginia. Of those in textile manufacturing, only 886 were nonwhite. For African Americans, employment at Dan River was sought after, but limited. Lena Page Lewis, the mother of Harry Michael Lewis, a sixteen-year old civil rights demonstrator arrested on July 11, 1963, earned $27 a week as a blower at the mill. [Source: 1963 Danville (Va.) Civil Rights Case Files. Individual Case Files. (J-R). Box 3.]

Courtesy of Danville Register. Danville, Virginia.

Danville Tobacco Workers.

African-American women often found employment as seasonal workers in tobacco receiving plants, supplementing their pay with unemployment compensation and wages from domestic work. Mamie Barton—the mother of fifteen-year-old Carolyn Sue Barton, arrested July 28, 1963, in the Danville civil rights protests—had worked twelve years at the Virginia Tobacco Company during the tobacco season, earning about $1,000 a year. In spring 1963, she was hired for domestic work at $15 per week and received eleven weeks of unemployment at $13 a week. [Source: 1963 Danville (Va.) Civil Rights Case Files. Individual Case Files. (A-D). Box 1.]

Courtesy of Danville Chamber of Commerce.

Civil Rights Protests, Richmond, Virginia, January 1, 1959.

Lawrence Clark received training in nonviolent civil rights protest from the Rev. Wyatt Tee Walker, pastor of Gillfield Church in Petersburg, Virginia, who in 1963 became the executive director of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) in Atlanta. On January 1, 1959, Rev. Walker led more than one thousand persons on a seventeen-block march to the state Capitol in Richmond. The demonstrators protested against the school closings in Virginia during massive resistance. State authorities did not meet with or respond to the demonstrators. The lack of reaction was an indication that direct action protests might not be as effective in the Commonwealth as in Deep South states where police violence generated media coverage and federal intervention. Instead, white officials in Virginia used legal mechanisms (such as the massive resistance laws) to resist desegregation—a tactic that ensnared activists in lengthy and costly court procedures. [Source: James H. Hershman, Jr. “Massive Resistance Meets Its Match: The Emergence of a Pro-Public School Majority,” in Matthew D. Lassiter and Andrew B. Lewis, The Moderate’s Dilemma: Massive Resistance to School Desegregation in Virginia (The University Press of Virginia: Charlottesville and London, 1998), 113–14.]

Courtesy of Richmond Times Dispatch. January 2, 1959.

A Brief History of African-American Education in Danville, Virginia, by Lawrence Mozell Clark, Ed.D.

African-American historians—Lawrence M. Clark among them—have enriched the cultural landscape of the Danville area with their research into local history. Dr. Clark wrote this account of African-American education in Danville from 1870 to the late 1960s; it extends from the Quaker-organized schools of Reconstruction to the segregated John Mercer Langston High School of the post–World War II era. Dr. Clark regards Langston High, during segregation, as a “mecca for the community, not only for the educational component, but also the social component.”

Courtesy of Lawrence M. Clark, Ed.D. [view .PDF version]

Lawrence M. Clark is a professor emeritus of mathematics education at North Carolina State University in Raleigh, North Carolina, where he served as associate provost and director of the school’s study abroad programs in Africa. He was born in Danville in 1934 and educated at William F. Grasty Elementary School and John M. Langston High School. After his 1952 graduation, Dr. Clark worked for two years at Dan River Mills as a cotton blower in the spinning room. He joined the U.S. Army (1954–56) and then, with support from the GI Bill, received a degree from Virginia State University in Petersburg (1956–60). He taught at Roanoke High School (1960–63); and then attended the Curry School of Education at the University of Virginia and received his doctorate in education. Dr. Clark was a professor at Virginia State (1965 and 1968–69); Norfolk State University (1969–70); and Florida State University (1970–74) before joining North Carolina State as associate provost and professor. He had a long and distinguished career at that institution and continued to work there in his retirement. Dr. Clark is also an ordained Baptist minister.